My TEDx Talk

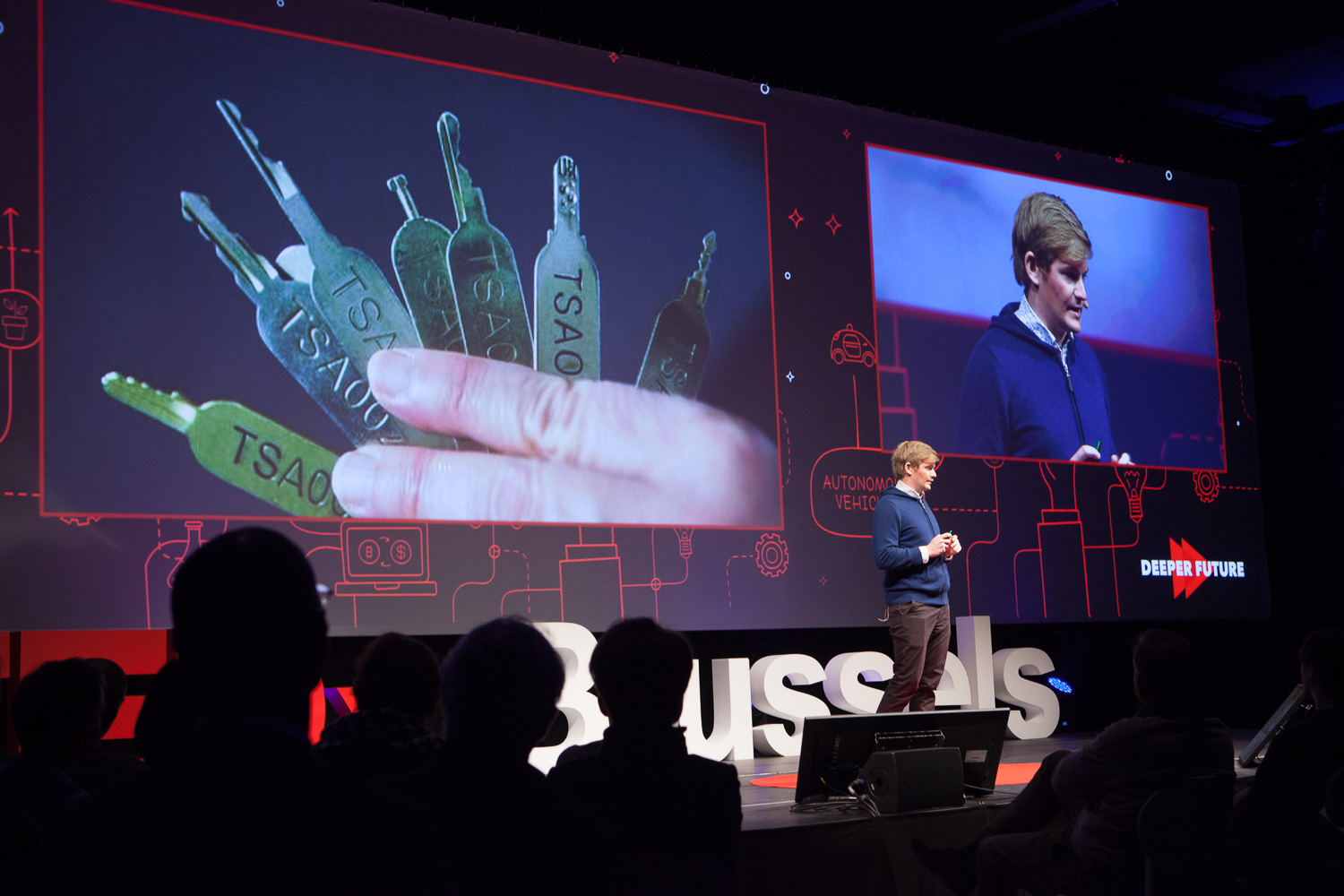

I gave a TEDx talk in Brussels on the 14th of March on the topic of master keys. Giving a TEDx talk is a very challenging and intimidating experience for anyone who is not an english native speaker since the bar is so high and most speakers have extensive public speaking experience.

Transcript

Last August, I was getting ready for a trip to the United States. After packing my luggage, I thought it would be useful to have a lock to protect some valuables in my luggage both while traveling and when I was hiking, leaving luggage behind. After a little bit of searching, I found my lock in the closet. It seemed the lock could be unlocked either by entering a digits combination or by opening it with a key. But I couldn’t remember where I left the key.

Well, it turned out, I didn’t have the key.

It wasn’t even given to me when I bought the lock.

After 9/11, the Travel Security Agency was created in the US to “protect the nation’s transportation system”. The TSA made two partnerships to develop locks that they could open to inspect luggage without having to break the locks. They would do this by adding a key slot that could only be opened by the TSA keys. These locks became mandatory when traveling to the United States and any other lock would just have to be destroyed.

While the measure was of good faith after a horrendous act of terrorism, the results were really disappointing.

TSA agents cut these locks off despite having the keys in more than 3500 cases in 2011 alone. A report concluded that there was a lot of uncertainty about the efficiency of the measures after observing increased luggage theft of both valuable goods as well as dangerous ones such as guns. Such thefts have raised concerns by national security officials that the same access might allow bombs to be placed aboard aircraft. And things got worse.

As I was traveling, someone on the Internet figured out that the Washington Post had posted pictures of the locks online, almost a year before.

From there, a range of events unravelled really quickly. Within 10 days, a group of lock-picking enthusiasts had modeled the keys in high resolution and used 3D printers to reproduce the set of keys. The model can now be downloaded from the code-sharing website GitHub and reproduced by anyone with a 3D printer, in minutes.

Whatever security I could have had from my lock was at that point completely gone. Of course, these locks aren’t very safe to begin with, but now not even lock picking skills are required to unlock them. Anyone can.

While these locks were meant to make us safer, they turned into a security nightmare. Let me give you another example.

This key, known to firefighters as the Yale 1620, gives you full access to any elevator in New York City. That means you can lock down any elevator in any skyscraper in NYC. But it also unlocks all the subway emergency exits and entries to any construction site in the city. Firefighters and national security officials have been describing the key as the ultimate terrorism tool if it ends up in the wrong hands.

Last September, a reporter from the New York Post revealed that the key could be acquired online for $8. I’m really not sure how people of New York City feel about realizing that they could be trapped at the top of a skyscraper or bombs could be placed in the subway tunnels by anyone willing to spend $8 on this key.

While both of these measures were trying to address very important issues, the way they were implemented ended up considerably weakening the security of these systems in general, instead of making them safer. The fundamental issue is the destruction of diversity which gives natural strength to the system.

Where previously a bad guy needed 300 million different keys to break into those locks, he now only needs to 3D print this set of keys. The TSA isn’t going to replace all 300 million locks that are unlockable with the keys that are available online. And New York City won’t be able to change hundreds of thousands of elevator locks overnight. While the city of New York is going to try and outlaw the ownership of those keys, about 50 people have already been arrested, thousands more will get a copy distributed as a file. The scale of these weaknesses make it so expensive and time-consuming to replace that about a decade will be needed to move away from those broken locks. And that is, if we get them to care enough.

In a recent piece in the Intercept, a TSA spokesperson reveals they don’t really care about the locks being compromised, citing them as being “peace of mind” devices, admitting that they never intended them to be safe anyways. Well, that’s reassuring.

There has to be a solution, there has to. As the quote says:

“For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple,”

and wrong …

This universal key, sometimes referred as golden key is a perfect example of this. On paper, a master key that would allow the TSA to unlock luggage in the search for bombs sounds completely reasonable, but in practice the key will leak and everybody will end up being less safe.

I can give you a lot of other examples. I’m not a lock picker, but I do work with locks, digital ones.

If I were to ask to anyone in the audience if I could take their smartphone and post the content of it online, I doubt anyone would take me up on that offer. Whereas your luggage lock may only protect a few valuables, your phone’s passcode protects your thoughts, memories and most personal moments and information. Compromise of phone backups have been ruining careers and lives. Our phones have become an extension of our brains, an extension of the mind. They remind us about what we forget. They illustrate our memories with the pictures we take. They keep our most personal secrets. Realizing that the mental process can occur somewhere else than in the brain is something we need to start accepting as we’re increasingly connected and dependent on technology to make decisions on a daily basis.

Our phones are also our gateway to the Internet. It is often said that the Internet was not designed for the scale it has today since it was primarily designed to meet the needs of the ARPANET network that was connecting labs across the US. But, in the context of the ARPANET, thousands of miles of Internet cables were considered trusted. The Internet was not designed with security in mind. While many of the assumptions were reasonable for the ARPANET, the threat model has changed quite a lot. The Internet has been militarized and bad guys are running all sorts of hacking and sniffing operations on the Internet backbone.

When email was invented, it was not designed with an adversarial threat model. In the email protocol, it’s trivial to send an email as someone else. Just google it, it will take you 5 minutes, or less.

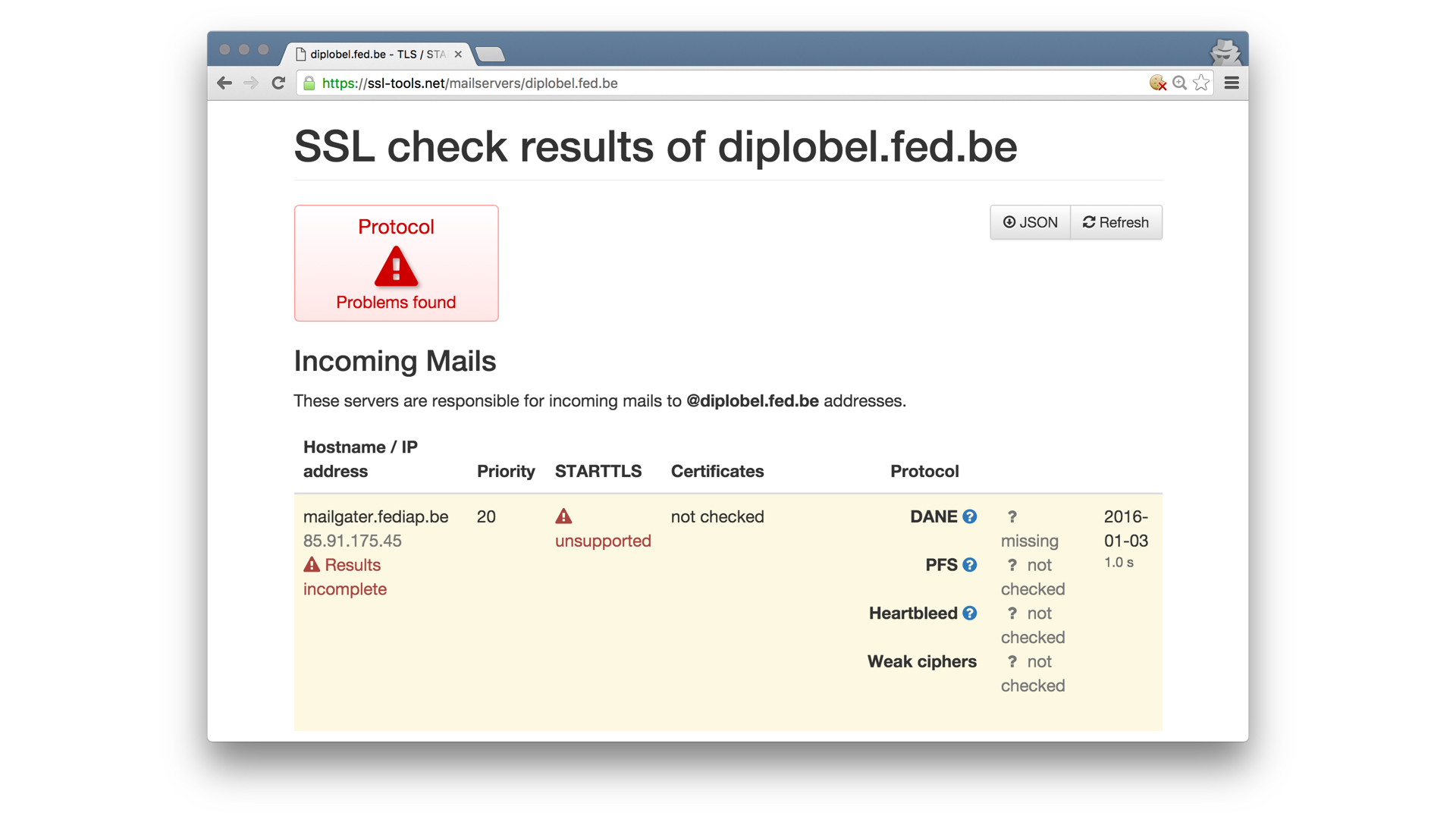

Email was not designed to be private either. A few weeks ago, I had to get paperwork filed with the Belgian Embassy. It turns out, that the email server of the diplomatic services worldwide doesn’t accept any mail over an encrypted connection. This means that anyone with network access between my email server and the Belgian Embassy email server can read my mail. This has to be fixed. Think about the consequences of this for a journalist or human rights worker in China or Iran.

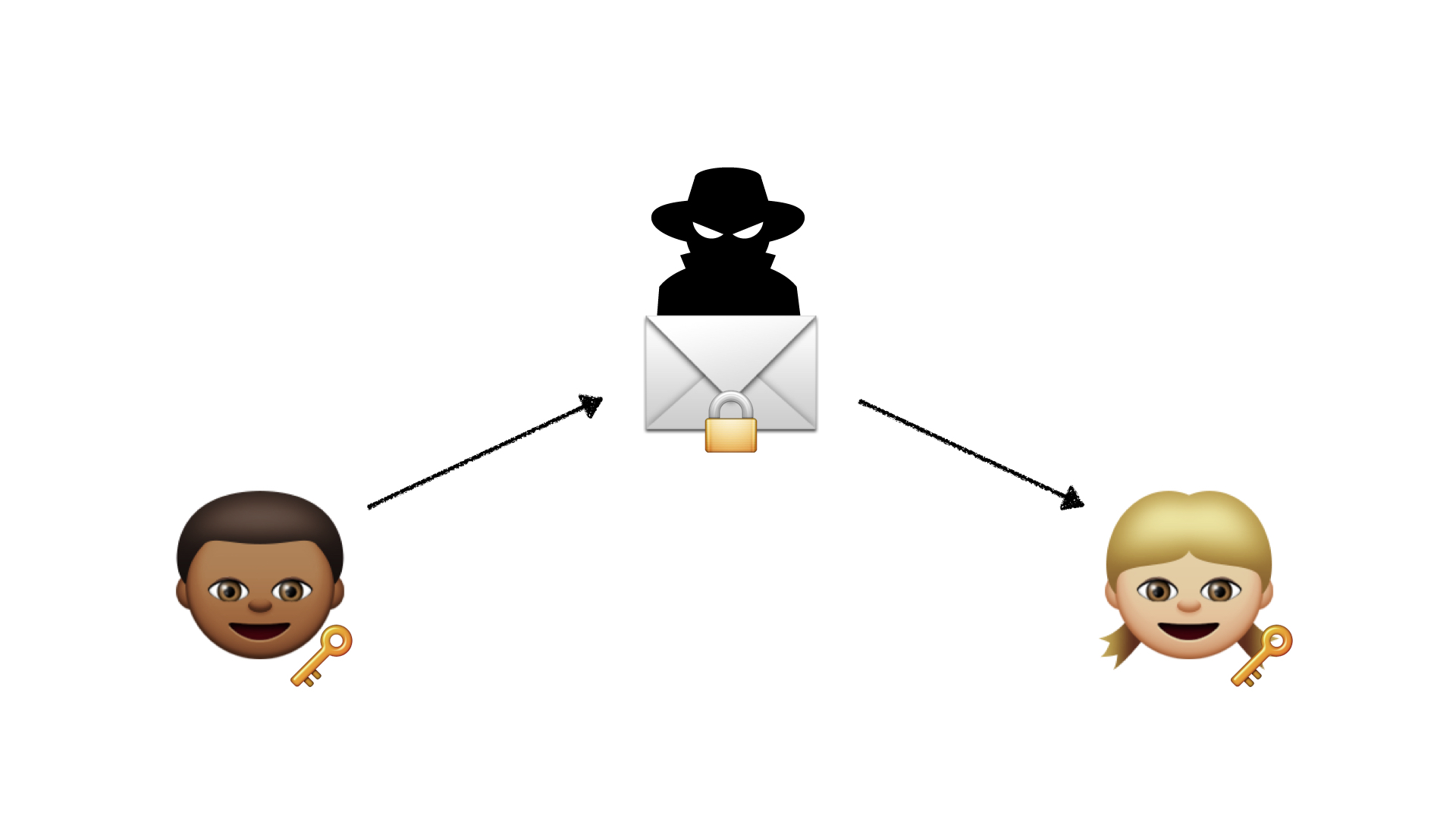

We need to go the full distance. We can design messaging services that work the way users would expect, where messages are only readable by the sender and the receiver, and not by the creepy postman who has been reading your mail.

The security community has been working on making a lot of these tools safer. And we’re getting there.

The debate about backdoors is often framed in the press as being a debate between privacy and security. This is a false dichotomy. Privacy is the power of being able to selectively disclose your identity to others. You can’t have privacy without security. You can’t have privacy if you can’t technically enforce ownership on your data. Backdoors won’t make us safer either : introducing a master key in the system, as we’ve seen, weakens the security for everyone. Making us more vulnerable to theft and espionage, at scale.

As companies and nations have been been failing to protect human rights such as privacy, we have been developing tools that protects those rights relying on the laws of nature, rather than the laws of nations. As these tools are making it into the mainstream, there is some push back against these technological advances from regulators and spying agencies who are unhappy about their job becoming harder. Now that the technology is mature, it is our duty to make sure that we can keep on using it to protect our rights.

Thank you.

Video

Special thanks to Romain Ruetschi, Jessica Jacobs, Dylan Bourgeois, Nadim Kobeissi, Xavier Damman and Arnaud Benard for reading and providing feedback on previous versions of this transcript.

Update (10th June 2016) : Added video of the talk.